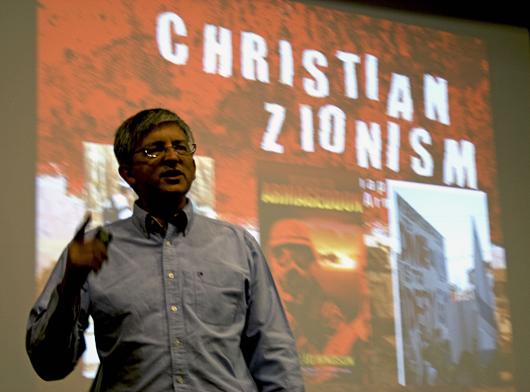

This week I am helping Porter Speakman promote the film With God on our Side at the invitation of Christian universities and churches in the USA.

Porter used my book Zion’s Christian Soldiers as one of the background sources for the film. The Bible Study Guide which accompanies the film is also based on the chapters of my book. Perhaps not surprisingly, some folk are not so happy that the spotlight has been turned on the dubious link between Christianity and Zionism.

I have been called a lot of things over the years. The more printable ones include a liberal, an anti-Semite, and a supercessionist (an advocate of Replacement theology). Lets begin by debunking these three red herrings.

Liberals and Evangelicals

Dispensationalists like to think they alone read the Bible literally and are more consistent than other Christians who, for example, ‘spiritualise’ away the promises made to the Israelites. That is probably why they get upset when some conservative evangelicals beg to differ. It would be more accurate to say that sometimes Dispensationalists accept a literal interpretation without acknowledging how Scripture interprets Scripture, for example, how Jesus and the Apostles use Old Testament promises and terminology in new ways. By imposing seven ‘dispensations’ on the Bible, some Dispensationalists seem to turn what is intended to be a unified plan of salvation for a sick world into separate isolation wards for different races.

Zionism and Anti-Semitism

It is true that at various times in the past, churches and church leaders have tolerated or incited anti-Semitism and even attacks on Jewish people. Racism is a sin and without excuse. Anti-Semitism must be repudiated unequivocally. However, we must not confuse apples and oranges. Anti-Zionism is not the same thing as anti-Semitism despite attempts to broaden the definition. Criticising a political system as racist is not necessarily racist. Judaism is a religious system. Israel is a sovereign nation. Zionism is a political system. These three are not synonymous. I respect Judaism, repudiate anti-Semitism, encourage interfaith dialogue and defend Israel’s right to exist within borders recognised by the international community and agreed with her neighbours. But like many Jews, I disagree with a political system which gives preference to expatriate Jews born elsewhere in the world, while denying the same rights to the Arab Palestinians born in the country itself. Jimmy Carter is not alone in describing the Zionism practiced by the present government of Israel as a form of apartheid.

Supercessionism or Replacement Theology

This is a favourite ‘straw man’ of Christian Zionists. They criticise their opponents for implying the Church has ‘replaced’ Israel. The implication is that the Jewish people cease to have any role within the purposes of God. This is clearly refuted in Romans 9-11.

The Scriptures are however unambiguous in distinguishing between the old and new covenants. In Hebrews, the writer says, “By calling this covenant “new,” he has made the first one obsolete; and what is obsolete and outdated will soon disappear.” (Hebrews 8:13). There is therefore, from a Christian perspective, no sense in which the old covenant can be viewed as still in force or applicable. On the night that Jesus was betrayed, after the supper he took the cup, saying, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood, which is poured out for you.” (Luke 22:20). When Jesus died on the cross, a new covenant was established with his precious blood that supercedes the basis of the old covenant. The writer to Hebrews continues, “For this reason Christ is the mediator of a new covenant, that those who are called may receive the promised eternal inheritance—now that he has died as a ransom to set them free from the sins committed under the first covenant.” (Hebrews 9:15).

Here then is the biblical basis for a kind of supecessionism. But notice the succession is first of all from one covenant to another, not from Israel to the Church. This is because both covenants were, in their first instance, made with the people of God who at that stage were predominantly Jewish. “The days are coming,” declares the LORD, “when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and with the house of Judah.” (Jeremiah 31:31). This is why Jesus initially sent his Apostles only to the Jews. “These twelve Jesus sent out with the following instructions: ‘Do not go among the Gentiles or enter any town of the Samaritans. Go rather to the lost sheep of Israel.’” (Matthew 10:5-6). But when the majority rejected his ministry, Jesus warned, “Therefore I tell you that the kingdom of God will be taken away from you and given to a people who will produce its fruit.” (Matthew 21:43). Jesus here describes the succession that would occur within a generation.

The apostle Peter, preaching after Pentecost, and citing Moses, similarly warned those who rejected Jesus, “Anyone who does not listen to him will be completely cut off from their people.” (Acts 3:23). Covenantalists believe there has only ever been one people of God – whether under the old or new covenant – and one way to God – by grace alone and through faith alone. Both Israel and the Church have been a mixed company of believers and unbelievers, Jews and Gentiles. Only God knows who is numbered among his faithful remnant. At various times in history it has been clearer than in others – for example when all but the family of Noah perished or the entire generation who entered Sinai, perished there apart from a handful. That is why many Covenantalists are uncomfortable describing the Church as the ‘New Israel’. The term never appears in the Bible. However, as we shall see in more detail in chapter 3, Peter uses language describing Israel and applies it to the Church.

“They stumble because they disobey the message—which is also what they were destined for. But you are a chosen people, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s special possession, that you may declare the praises of him who called you out of darkness into his wonderful light. Once you were not a people, but now you are the people of God; once you had not received mercy, but now you have received mercy.” (1 Peter 2:8-10)

It is not that the Church has replaced Israel. Rather, in the new covenant church, God has fulfilled the promises originally made to the old covenant church. So, for example, when Jesus affirms Peter’s declaration of faith and says, “on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of death will not overcome it.” (Matthew 16:18), the word translated for ‘church’ in Greek is ‘ekklesia’ – the very word used in the Greek Old Testament to describe God’s people. No – Covenantalists are not liberal, anti-Semitic or into ‘replacement’ theology.

Is there an Elephant in the Room?

I hope you are beginning to see why this is such an important subject. There is a giant elephant in the room and its time we started talking about it. As I intimated in the foreword, fear of being accused of anti-Semitism for challenging the Zionist agenda is enough to keep many evangelicals under their beds. In my view, and that of an increasing number of other evangelicals, it is time to speak out because Christian Zionism has become a formidable and dangerous movement. Portraying the modern state of Israel as God’s chosen people on earth, the role of the Church has been reduced in the eyes of many to providing moral and biblical justification for Israel’s colonization of Palestine. Those who oppose her are demonised.

While not all Christian Zionists endorse the apocalyptic views of Hal Lindsey and Tim LaHaye, the movement as a whole is nevertheless leading the West, and the Church with it, into a confrontation with Islam. Using biblical terminology to justify a preemptive global war against ‘the Axis of Evil’ merely reinforces stereotypes, fuels extremism, incites fundamentalism and increases the likelihood of nuclear war. Do I think the Bible predicts all this? No I don’t.

It is not an understatement to say that what is at stake is our understanding of the gospel, the centrality of the cross, the role of the Church and the nature of our missionary mandate, not least, to the beloved Jewish people.

Taken from the Introduction to Zion’s Christian Soldiers